The FT reported last week that –for the first time—the S&P 500 has outperformed the State Street private markets index on all time horizons that it typically presents.

In the AltView’s eyes, the State Street index seems a credible measure of performance—more so than some others we’ve seen, like those connected with private equity promoters.

Not all time horizons are created equal. Quarterly and one year results? Who cares. 10 year results: we pay attention. We remind investors: a wee increment of PE outperformance vs. public equities shouldn’t satisfy; a sensible standard is much higher.

There will always be a way to make the sobering long-term results look better. If it does not exist ex-ante, a new method will be invented.

PE promoter-propgandists and complicit PE-investor-rationalizers(1) might argue that the Russell 2000 (small capitalization) index is more suitable. PE veterans like Ludovic Phalippou are around to remind us that many PE promoters switched from benchmarking against the S&P 500 to the MSCI ACWI or Russell 2000 index once beating the S&P got tougher.

We’d argue that the Russell 2000 seems like a BS index for, well, most anybody. But definitely BS for Private equity firms.

Why? 42% of the member companies are unprofitable, making them, errr, incompatible with leveraged buyouts. They fail the “appropriate” test; CFA candidates and charterholders eager to embrace industry best practices would avoid using it.

If you are looking for profitable small cap companies, the S&P 600 is a better option. And guess what, guys? The S&P 600 returns have been notably better than the R2000: 1.75% per annum since 1994.

We’ve even heard about small cap managers that invest to track the S&P 600 while benchmarking against the R2000. Cynical, but brilliant! Maybe those managers are cousins of the genius NAV-squeezers of the private equity secondary world.

What’s in PE?

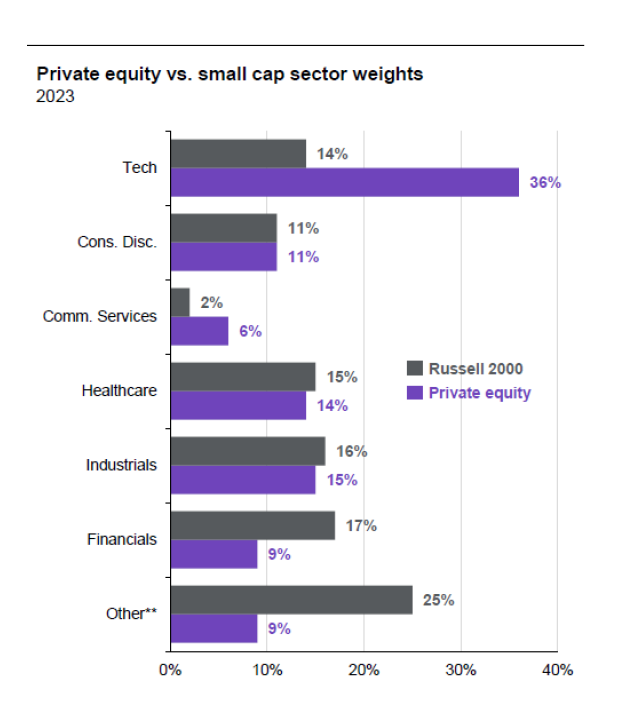

Sector weightings are another issue. According to the (excellent) JP Morgan guide to alternatives, the largest sector weighting in PE is tech. By a mile. In this way too, the R2000 fails the “appropriate” test.

Benchmarking can be tricky, but determining that the R2000 is not a sensible benchmark for PE investments is not.

It’s the future that matters

That’s all in the past. We’ll keep banging this drum for Alts investors of the future: if you invest in assets like private equity, you should be able to quantify and WRITE DOWN, your expected outperformance vs. public markets. If you hire a consultant to do the work, they should have an expectation for the asset class overall and their expected return for the funds they pick (presumably better than the expected average return for PE overall).

If using a consultant, you should consider your consultant’s opinions re: Alts returns with skepticism, particularly if they make more money managing/advising on alts than on traditional investments (as most do). YOU are responsible for quantifying and assessing their agency conflict when investing in Alts vs. boring, low-cost, liquid, flexible investments.

This approach is not a trap or designed to get yourself fired/sued at some future date. Think of it as a way to avoid bad decisions TODAY. Trust us: great freedom (and probably better risk adjusted performance) may come from deciding Alts aren’t worth the bother.

At the AltView, we aren’t in a position to say what the market thinks. If we were, we’d be on CNBC all the time. Still, we read a lot and will admit that we sense a naïve view among many that future private equity returns will be ok to good. It feels like a lazy, “mean reversion will happen won’t it”-“I don’t want to talk about performance rn”—"our last fund is still investing ..ooof”-- kind of a vibe.

Framing future returns isn’t that hard. Two key inputs for PE investors are:

1. The valuations of companies that PE investors want to own (or currently own) and

2. Borrowing costs.

The historical valuations for PE investors (thank you JP Morgan) are below. Note the nice tailwind from the GFC to 2022. Could that happen again? Sure. Are you comfortable predicting anything remotely approaching it?

The lack of recent PE exists is described as a logjam, clog, funk, whatever. Seems to us, if GPs wanted to sell portfolio holdings, all they have to do is lower the asking price.

This kind of standoff reminds us of a conversation between the then-Harvard Endowment boss, Jane Mendillo, and a prospective buyer of some of Harvard’s Alts, as recounted in a GFC-era Vanity Fair article and quoted in Andrew Ang’s excellent (and newly-relevant) case study, “Liquidating Harvard.”

Money Manager: Hey look, I’ll buy it back from you. I’ll buy my interest back.

Mendillo: Great.

Money Manager: Here, I think it’s worth you know, today the (book) value is a dollar, so I’ll pay you 50 cents.

Mendillo: Then why would I sell it?

Money Manager: Well, why are you? I don’t know. You’re the one who wants to sell, not me. If you guys want to sell, I’m happy to rip your lungs out. If you are desperate, I’m a buyer.

Mendillo: Well, we’re not desperate.

We are not suggesting that the current environment is as problematic as the GFC. Yet it seems like the asset owners are unreasonable, not the prospective buyers; as the chart shows, valuations have not declined by much.

We are bad at math

It’s true. So we used a spreadsheet to run some basic LBO numbers, inspired by AQR’s approach in the Journal of Alternative Investing; their template is below. When we did the CAIA curriculum a few years back, this was our favorite reading.

When you plug in a higher cost of debt, and figure little to no multiple expansion, the results are sobering. The above table is from way back when money was free. AQR’s most recent PE return expectations are below.

AQRs Public equity return expectation is now higher than PE. Mrs. Alt View hates it when we say this, but…its just math!

And yet, AQR seems alone in these assumptions. All of the others we’ve seen have a private equity return expectations higher than public equity.

The lack of curiosity among PE investors about the AQR outlier is noteworthy. Is it ostrich behavior? Also: as far as we know, AQR does not manage private equity. Could the lack of agency bias make it easier to tell the truth?

_______________

(1) Investor-rationalizer: An investor-rationalizer can take many forms. One example: an investor who started out with high return expectations (like, say, a benchmark of global equities +4% per annum for PE) but now chooses a much lower standard like, say, global equity markets +0%. This approach insures alpha and is sure to bring on annual celebrations and back-slapping. We are going to work on a better name for this creature; quality nominations might win an AltView mug (with our new badass logo).

Resources:

FT Article:

State Street Private Equity Index:

https://globalmarkets.statestreet.com/portal/peindex/

S&P 600:

R2000 profitability:

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/the-share-of-u-s-companies-with-negative-earnings/

JPM Guide to Alternatives:

https://am.jpmorgan.com/us/en/asset-management/adv/insights/market-insights/guide-to-alternatives/

Liquidating Harvard (Andrew Ang)

https://caseworks.business.columbia.edu/caseworks/liquidating-harvard

Ilmanen on expected returns for private equity:

AQR, Capital Markets Assumptions:

Who would've guessed that the battle at the top is a bunch of sales people

Likewise, I have pondered what the return premium encompasses (encompassed?). If it were a pure illiquidity premium, it would be more or less persistent barring shocks and lags in pricing. As this article alludes to, it is a catch-all that includes financial engineering, leverage, capacity for dividend recaps, some operational improvement/expertise, etc, etc, etc. Not all are persistent either, as we are learning.